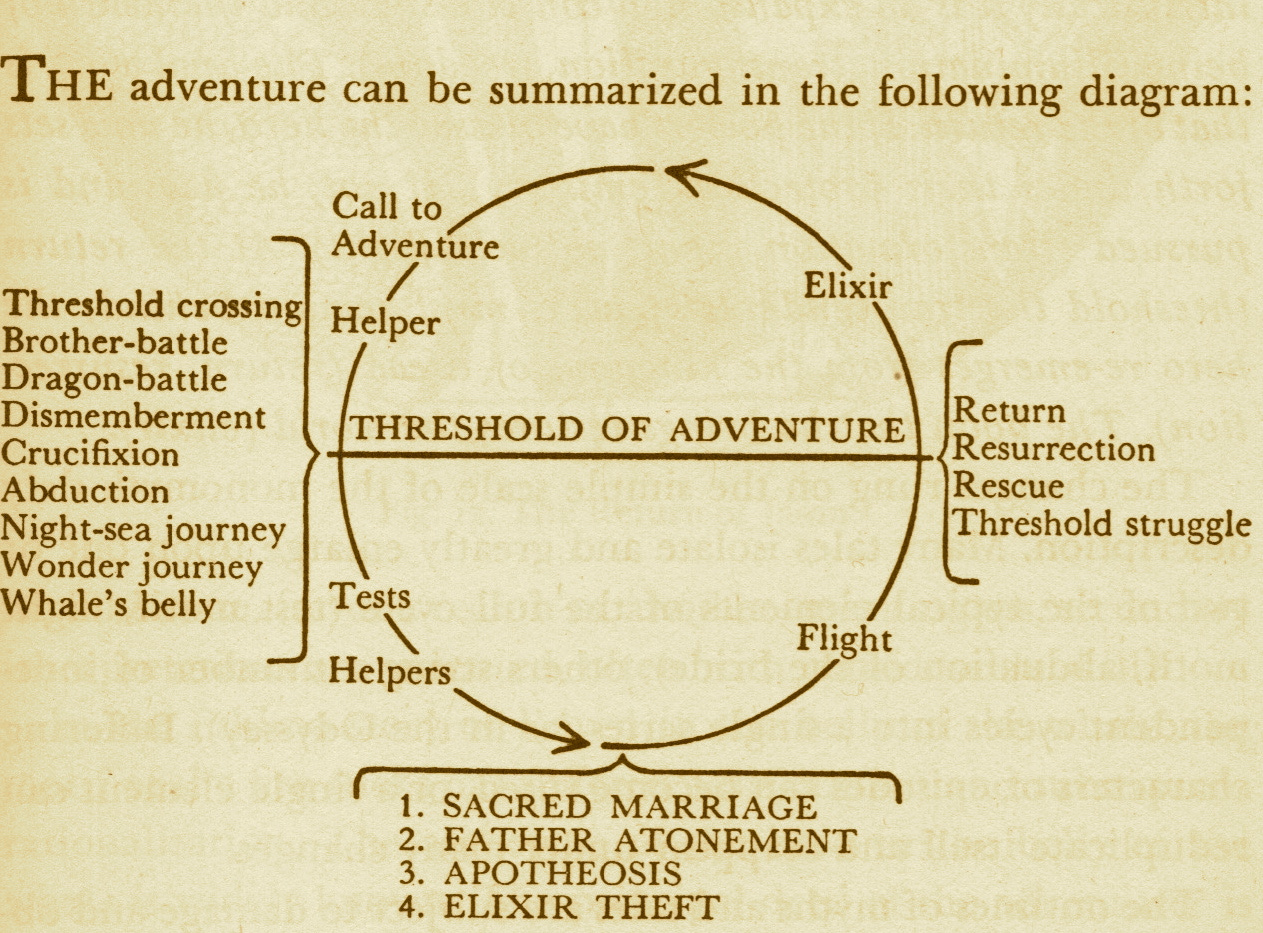

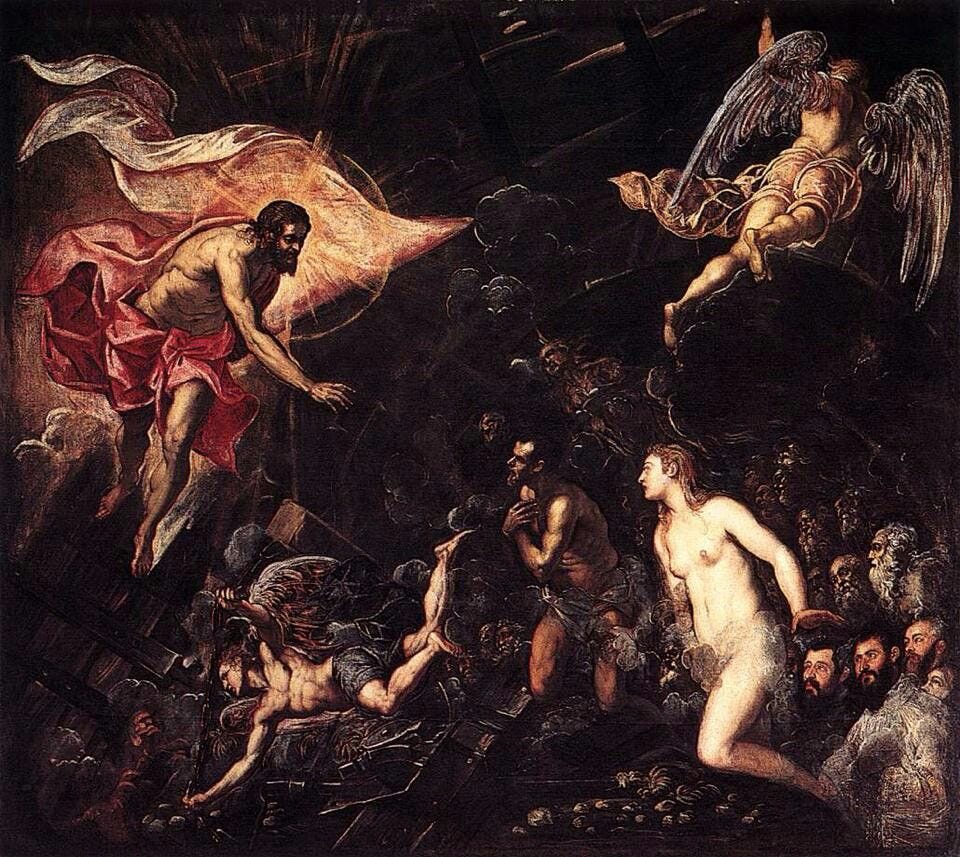

“The mythological hero, setting forth from his commonday hut or castle, is lured, carried away, or else voluntarily proceeds, to the threshold of adventure. There he encounters a shadow presence that guards the passage.

The hero may defeat or conciliate this power and go alive into the kingdom of the dark or be slain by the opponent and descend in death. Beyond the threshold, then, the hero journeys through a world of unfamiliar yet strangely intimate forces, some of which will severely threaten him, some of which give magical aid.

When he arrives at the nadir of the mythological round, he undergoes a supreme ordeal and gains his reward. The triumph may be represented as the hero's sexual union with the goddess-mother of the world, his recognition by the father-creator, his own divinization, or again -- if the powers have remained unfriendly to him -- his theft of the boon he came to gain; intrinsically it is an expansion of consciousness and therewith of being.

The final work is that of the return. If the powers have blessed the hero, he now sets forth under their protection; if not, he flees and is pursued. At the return threshold the transcendental powers must remain behind; the hero re-emerges from the kingdom of dread. The boon that he brings restores the world.”

I think I’ve heard this one before. Countless times, actually.

You’ve heard it as well, though you may not realize it. If the above reads like a bunch of stereotypes, like a sequence of tropes, that’s because they are. Really though, they are much more than that. They form an archetypal story. A myth.

The above text comes from Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. It’s his summary of the hero’s journey - the main subject of the book. Campbell argues that the hero’s journey is the archetypal structure behind almost all myths and legends, a universal story structure that appears throughout all of human history and in every corner of the world.

The hero’s journey is not the only archetypal story. There are others, such as the great flood or deluge. We all know Noah and the great flood from the Bible, but the same story is told in Sumeria as the tale of Utnapishtim, in India as the tale of Manu, and in the Aztec world as the tale of Coxcox. Many of our great tales are retellings of these archetypal stories. These are our myths, our legends, our folklore. But it is not only these ancient things that reflect the archetypal stories - much of our modern pop culture continues this tradition. The works of modern pop culture that become classics, the big hits, whether in literature or on the big screen, are almost exclusively tales that follow these ancient patterns.

Star Wars is a preeminent example. It may be set a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, but its structure is quite close to home. In fact, George Lucas has admitted that he was influenced by Campbell, and that he intentionally used the hero’s journey structure for the Star Wars screenplay. Star Wars has all the essential archetypal beats: the orphaned hero, the wise mentors, the confrontation and reconciliation with the lost father, the descent into the underworld, etc.

Harry Potter is another. Arguably the twenty-first century’s defining pop culture phenomenon, it follows the mythic structures of the Hero’s Journey down to the letter. The orphaned child who will be the chosen one, Dumbledore as the wise mentor, the crossing of the threshold from the mundane world of the Muggles into the magical world of Hogwarts, the dark-twin myth underlying Voldemort, and Harry’s conquering of Death in the final installment - all ancient and archetypal stuff.

More recently, the Dune films took pop culture by storm, and are yet again an example of a standard Hero’s Journey story becoming a huge hit. Another orphan-hero “chosen one”, another journey into the wilderness to claim an ancient power and fulfill a prophecy.

The entire fantasy genre draws deeply from this mythic well. Individual stories may not follow Campbell’s Hero’s Journey formula exactly, but the locations and characters are all mythic in nature. Elves in enchanted forests, dwarves in the mountains, advanced sea-faring kingdoms, wandering wizards, dark lords in high towers, orcs haunting dungeons, dragons lurking in deep caves.

Our favorite modern stories are not really all that different from ancient legends and folktales. They follow the same patterns and are filled with the same archetypal characters. And the stories that draw our derision, like Amazon’s The Rings of Power, always deviate from these patterns. The archetypes keep popping up, and we can’t get enough of them when they do. There is something keeping us tied to these mythic patterns and archetypes, to these great tales.

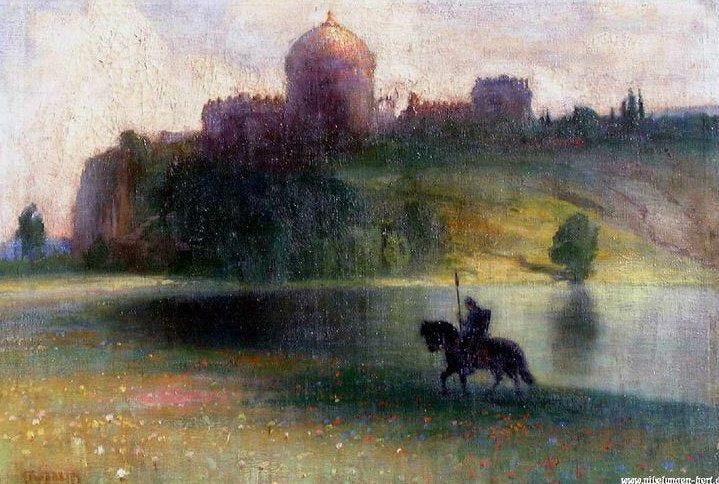

Tales of swords and rain, grim towers, dark forests.

Tales of deluge and darkness and the darkening of the Westlands.

Tales of war and sorrow.

Tales of orphaned heroes and journeys into the unknown.

Why do we care so much about these stories, and what drives us to return to them again and again? And what exactly are myths, where do they come from, what is their role in our lives? And perhaps most importantly of all … is any of it real?

Into The Unconscious

A popular explanation for the constant recurrence of these archetypal stories in our lives, our myths, and our popular culture comes from the realm of psychology. Carl Jung called it the collective unconscious, the shared subconscious human mind inhabited by the archetypes embodying our primal instincts. By archetypes, Jung meant the inborn, universal ideas and patterns that all human beings inherit, regardless of personal experience or upbringing. The mother, the trickster, the old sage, and the great flood are all examples of Jungian archetypes. Joseph Campbell adopts Jung’s psychological frame in The Hero With a Thousand Faces, which is to be expected as Campbell was profoundly influenced by Jungian psychoanalysis.

Jung believed that the worldwide similarities of myths, shared between completely disconnected cultures, were expressions of this collective unconscious, and demonstrations of its existence. Archetypal stories continually reappear because they emerge from deep within the human mind, having evolved inside of us over the eons. The symbols and patterns forming the archetypes manifest in our dreams and in the myths we tell about the cosmos and ourselves.

The Jungian approach relegates the archetypes to purely mental constructs, which then express themselves in the behavior of human beings. Myth is not “real” in this framework in the sense you’d usually use the word “real”. A Jungian thinker like Jordan Peterson might tell you that myths, being archetypal, are “realer than real” or “truer than true”, and they are correct, but try to get them to answer whether any of this stuff is literally (as in historically) true and they’ll squirm.

When everything becomes symbolic of the inner quest of the psyche for acceptance, self-actualization, and enlightenment, does it not also become meaningless, because it is no longer tangible? The psychological approach is inherently atheistic, as its basic premise is materialistic. It could also be classified as gnostic, as it puts the quest for “enlightenment” or secret knowledge - in this case, of one’s own unconscious and true self - as the highest good while rejecting the importance of the physical world and tangible reality. It is a spiritual quest with no real bedrock of belief in the supernatural and therefore no real destination. Jung believed the spiritual “quest” that Campbell describes as the “hero’s journey” to be the process of the individual’s discovery and fulfillment of their deep, innate potential, which is essentially the view that Campbell adopted himself. But is that all it is? To Campbell’s credit, he does admit near the end of his book that a psychological approach is not enough all on its own:

“Mythology has been interpreted by the modern intellect as a primitive, fumbling effort to explain the world of nature (Frazer); as a production of poetical fantasy from prehistoric times, misunderstood by succeeding ages (Muller); as a repository of allegorical instruction, to shape the individual to his group (Durkheim); as a group dream, symptomatic of archetypal urges within the depths of the human psyche (Jung); as the traditional vehicle of man's profoundest metaphysical insights (Coomaraswamy); and as God's Revelation to His children (the Church). Mythology is all of these. The various judgments are determined by the viewpoints of the judges. For when scrutinized in terms not of what it is but of how it functions, of how it has served mankind in the past, of how it may serve today, mythology shows itself to be as amenable as life itself to the obsessions and requirements of the individual, the race, the age.”

But something is lacking in this list: the possibility that myths could be fundamentally true - real in a historical, cosmic, literal sense. Campbell, like many others, is limited by a lack of faith. He mentions myth being “God’s revelation to his children” but only as one function among many. There is only so far you can go as an atheist, as a gnostic, or as one who is vaguely ‘spiritual but not religious’.

Interestingly, Jung seems to have realized this at some level later in his career. He began to suspect that phenomena he had considered purely symbolic, like astrology, had more to them than he had previously been prepared to believe. Jung's concept of synchronicity, which involves a confluence between events with an inner, psychological meaningfulness and an external, objective aspect, leads to a conclusion that takes us across the threshold of science and into the supernatural.

Most interestingly, Jung’s “Red Book” describes his experiences with real spiritual events, like visions and hearing voices. The book covers his experiments over a 17-year period, from 1913 to 1930. During this period he left the stale realm of pure academia and began experimenting with “active imagination” or self-induced dream states where he would explore the unconscious or symbolic realm. Some have called this period of Jung’s life a spasm of madness, a criticism Jung shrugged off as superficial and trite. Speaking about this time, Jung stated:

“The years ... when I pursued the inner images, were the most important time of my life. Everything else is to be derived from this. It began at that time, and the later details hardly matter anymore. My entire life consisted in elaborating what had burst forth from the unconscious and flooded me like an enigmatic stream and threatened to break me. That was the stuff and material for more than only one life. Everything later was merely the outer classification, scientific elaboration, and the integration into life. But the numinous beginning, which contained everything, was then.”

I find it unsurprising that Jung went down this path. Man desires more than symbols. We desire the real thing.

Imagine trying to convince your twelve-year-old son that the reason he loves tales of St. George slaying dragons, or Thor arm-wrestling frost giants, or Perseus beheading Medusa, is because they represent the spiritual battle against his inner demons and passions. You would be partially correct, but you’d also bore your son to tears. Your son doesn’t care about all that. He wants to hear that there were actual dragons and monsters from the deepest pits of Hades that were slain by actual heroes with hot blood pumping through their veins, their faces wet with sweat and grimy with soot. Is he simply immature for wanting to hear this, as if he is just a child that needs to grow up and understand the “deeper” spiritual truths? Or do children love Faerie stories precisely because they love true stories? Is it children who want to escape the “real world” … or the adults?

The answer to the riddle of myth must lay deeper than psychoanalysis can take us. As a Christian, I believe in a divinely-ordered universe, and therefore I must believe in a cosmic pattern, in primordial truths, in archetypes that are more than mere symbols, that are seared into every aspect of the cosmos by the immanent and transcendent God who created and animates it.

If myth is part of this “cosmic pattern”, and if we assume that fundamental truths and symbols flow through everything in creation, then must not the archetypal stories of our myths, by necessity, also manifest in the tangible world beyond mere symbolism? Viewed in this light, should we not expect myths to be about real events just as much as they are about the archetypes and symbols that dwell in our collective unconscious? To explore this, we’ll have to embark on our own hero’s journey, leaving the comfortable world of “academically” acceptable ideas and crossing the threshold into the unknown. We must face the question- did our myths actually happen?

History Becomes Legend, Legend Becomes Myth…

I want you to imagine, what if it was all real? What if our myths are really our dim memories of prehistory? What if we tell the same stories over and over again because they are the sagas of our ancestors, so essential to who we are that they have become, as Jung might say, embedded in our psyches? What if all great stories are only a retelling?

The myths of cultures all around the globe contain similar elements, too akin to one another to ignore. Fair races of elf-like folk, wars with giants, a great deluge, dwarves in the mountains, wisdom bringers that teach the arts of civilization. Many theories have been proposed for why myths are shared by cultures that have no contact with one another, but the simplest conclusion is always ignored: that we simply remember our history.

In 1930’s Australia, scientists found that local tribes refused to approach the Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve. This is the site where a huge meteorite exploded 4700 years ago with the force of a small nuclear bomb. The indigenous Australians have no written history, but we know they witnessed this event. How do we know? Because the reason they will not approach the craters is that they forbid going near the site where the “fire-devil” rained down judgment on the land. They have legends to this day that the fire-devil will send down fiery destruction on any who break the sacred laws. This fascinating story demonstrates a case in which myth absolutely contains an element of true oral history.

In a similar vein, the Irish tales of the Tuatha-de-danann tell of an advanced race of fair folk that came and conquered Ireland in the distant past, bringing with them technology and weaponry far beyond what the original inhabitants possessed. Could this myth be an oral history of the Indo-European invasions that displaced the neolithic inhabitants of Ireland? It certainly adds up.

Could an archetype like the “thunderbolt” of the gods be a memory of the human invention of projectile weapons that allowed our forebears to gain the upper hand over monstrous prehistoric enemies? What if our dragon-slaying hero myths are memories of battles against ferocious man-eating reptiles?

Could the myths of familial wars in the heavens be a memory of the civil wars of advanced races, perhaps like those from Plato’s Atlantis, races that would have seemed like gods to the simpler hunter-gatherer peoples surrounding them? Could Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades have been actual brothers fighting over a literal kingdom? What about Norse tales of the wars between the jötnar and the Ӕsir? Are these faded memories of wars between rival human clans, or of wars between humans and other hominid species?

Researchers like Randall Carlson and Graham Hancock have exploded in popularity with their explorations of the hypothesis that the universal world legends of great cataclysms and floods are not mere fantasy but based in geologically and archaeologically verifiable fact. They promote the Younger Dryas impact hypothesis (YDIH), which is a theory that a swarm of comets hit the Earth around 12,900 years ago. This cosmic bombardment devastated wide swaths of North America and Eurasia, igniting a conflagration of wildfires that swept the land clean and drove the Pleistocene megafauna to extinction; dust loading of the atmosphere then led to the abrupt global cooling and temporary glacial rebound paleoclimatologists had previously identified as the Younger Dryas event. Carlson and Hancock theorize that these events could be the basis of the “great deluge” myths seen all around the world. They’ve also posited that mythical world-destroying “dragons” could be memories of long-tailed comets streaking across the prehistoric sky.

Archaeologists have found evidence that the tale of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah may originate with the mysterious destruction by cosmic bombardment of a neolithic city at the Abu Hureyra site in Syria. We thought Troy was a myth, until the ruins of the ancient city were found, complete with a layer of the ancient city that shows that the city was once destroyed in a great fire. Myths have a way of being proven as history.

If many of the myths are based on history, what if the Jungian archetypes are actually downstream from real events that inspired them? If we remember lost history in our myths and in our psyches, does that mean we may have the ability to recall lost stories? Do we have the ability to “remember” forgotten tales?

Who better to ask than Professor Tolkien.

Dreaming of Middle-Earth

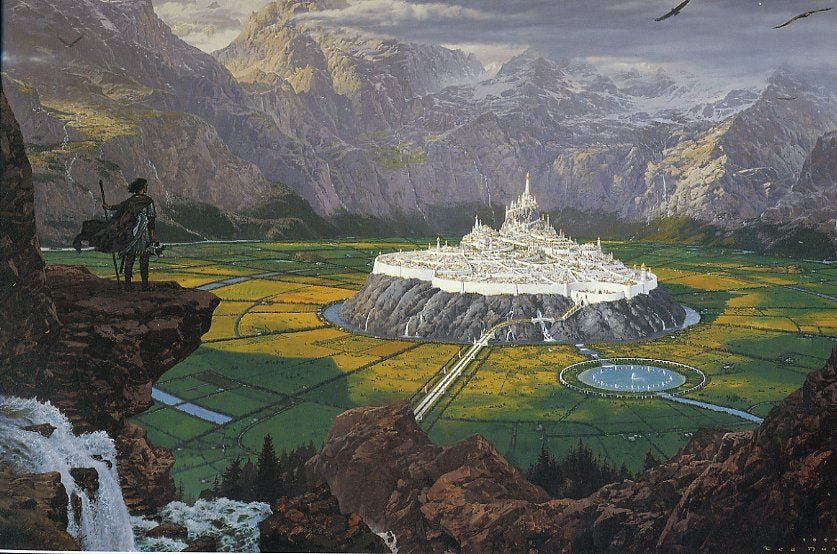

Tolkien is commonly considered the father of modern fantasy, but what if his stories are something else entirely? What if they are more than fantasy?

In my series “The Lost History of Middle-Earth” I’ve been exploring a number of mysterious connections between J.R.R Tolkien’s works and the real-life ancient history of Europe. The professor may have been up to something that he never admitted to… or perhaps something he did not fully understand, himself.

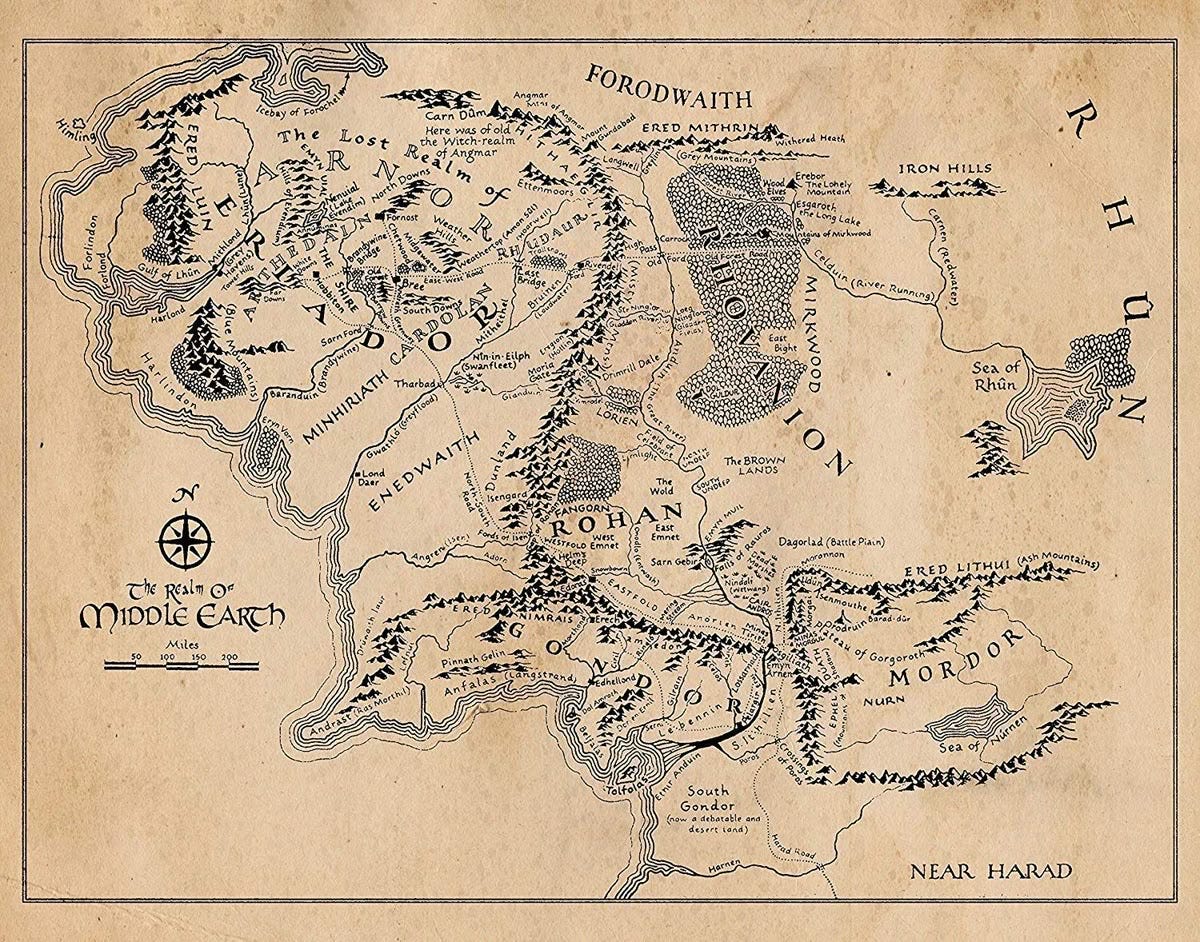

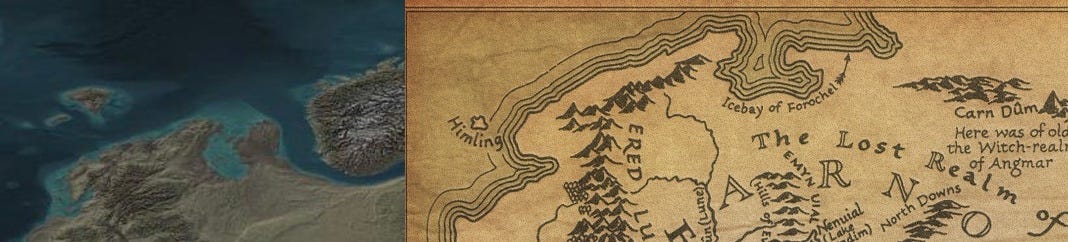

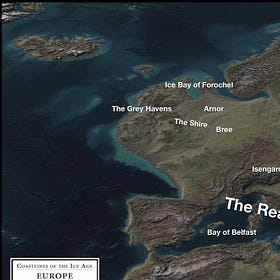

Firstly, I do not believe that “Middle-Earth” is meant to be a fictional place. Tolkien always insisted that his stories were myths of a forgotten age of our real world, but that idea has always been treated like it was just a cute frame story of his, and not something to be taken seriously. But what if the professor really meant it more than he let on to the public? One day, I was playing around trying to find historical maps of Europe that looked similar to Middle-Earth, and I found more than I bargained for. As it turns out, the geography of Tolkien’s Middle-Earth matches the landscape of Ice-Age Eurasia so closely that it seems impossible that it could be a mere coincidence. Using a map scale of Middle-Earth that covers Ice-Age Europe from Britain to Anatolia matches these two regions with the Shire and with Mordor. The symbolism matches up exactly, with the Shire representing Tolkien’s homeland of England, and Anatolia representing the far eastern land that had been taken over by a dark power (as the Turks did to Byzantium).

Similarly, using this map projection, Mirkwood falls in Ukraine north of the Black Sea, which is exactly where the Norse Sagas attested it to be in real life. The Atlakviða ("The Lay of Atli", in the Elder Edda) and the Hlöðskviða ("The Battle of the Goths and Huns", in Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks) both mention that the Mirkwood was beside the Danpar, the River Dnieper, which runs through Ukraine to the Black Sea. The Sea of Rhün appears to represent the Caspian Sea, while the lands of Khand and Harad are the near east.

But the geography of Middle-Earth matches Ice Age Europe in much more specific ways than just the general layout. Even the tiny Icebay of Forochel lines up directly with a real bay in the northern landscape of Ice Age Europe. Compare the main bays and the smaller bays in the west on the bottom left of the images above. Why does Tolkien’s map include a tiny ice bay, one with little mention in his stories, that just so happens to match up perfectly with this ancient Ice Age bay, long lost under the ocean? I don’t think it could be happenstance. Also notice the island “Himling” that Tolkien has included, similar in location to the Faroe Islands seen in the real Ice Age landscape. It is one of the only islands included on Tolkien’s map, and so was certainly included with intention. It stretches credulity that so many small details could align purely by accident.

How Tolkien Disguised Ice-Age Europe as Middle-Earth

Maps of Middle-Earth have been laid over maps of Europe before. They’re never very interesting, because they seem to prove that Tolkien’s world was nothing close to a one-to-one representation of an ancient Europe. They usually place the Shire (per Tolkien’s instruction) at Oxford, but make no attempt to fit in anything else in a way that makes sense.

As I continued to dig into this idea, closer examination revealed correspondences that were even more specific. It appears that the tale of Turin Turamabar, and his final resting place of Tol Morwen, may be based on a real, minuscule island in the Atlantic: Rockall. In fact, Tolkien left clues about it in The Silmarillion. This tiny footnote of a legend in Tolkien’s legendarium referencing this tiny real world island may be the most convincing piece of evidence I’ve found. While you could try to explain the rest away by saying Tolkien was simply inspired by European legends, no such explanation can be applied in this case where Tolkien can be seen to explicitly be writing about Rockall. Tolkien went out of his way to write a story about a tiny, insignificant island in the real world, and then never told anyone about it. Why?

Rockall: The Ruin of Beleriand, Hy Brasil, and the Grave of Turin Turambar

"And some things that should not have been forgotten were lost. History became legend. Legend became myth."

Tolkien’s works also accurately describe many real-world lost lands. The “lost realm of Arnor” in northwestern Middle-Earth perfectly matches up with “Doggerland”, the submerged landmass that lies under the North Sea. Arnor’s geography even matches the mountains and great lake that Doggerland would have had long ago. It matches so exactly that it cannot be coincidence. No, Tolkien knew that Arnor was really Doggerland. The question is not if, but why, and how?

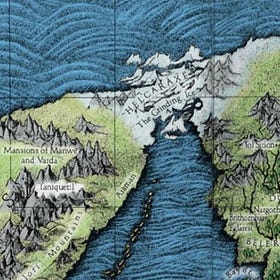

His description of the shape and location of the sunken isle of Númenor, his Atlantis, sounds very much like the Mid-Atlantic ridge, where many Atlantean researches have posited the real Atlantis may have been. Númenor is described as star-shaped, and at a certain sea level the Mid-Atlantic ridge is actually star-shaped as well. Did Tolkien really believe in the existence of Atlantis, were the tales of Númenor his attempt to tell its true story?

Tolkien’s description of Beleriand sounds very much like it may be based on the Rockall Plateau in the Atlantic. Tolkien also includes hints in The Lord of the Rings as to the real origins of the Black Sea, hinting that they were once the “Brown Lands” north of Mordor.

These connections are all too specific to be coincidences. Was Tolkien intentionally writing legends about the lost history of European lands? Did he intended his stories to be “true” myths about forgotten eras of European history rather than fantasies set in a fictional world?

Lost Lands of Arda

My first entry in this series detailed how Tolkien’s Middle-Earth, when correctly scaled, perfectly matches the landscape of Ice-Age Europe. Tolkien’s placement of mythic locations such as Mirkwood also matches their attested locations in ancient Europe.

But how did Tolkien do all of this? Did he know the landscape of Ice Age Europe, and secretly mimic it? Did he find records of lost histories in Oxford libraries? Did he somehow do all of this subconsciously, through his extensive knowledge of myth and prehistory? Or is it all an unfathomably unlikely coincidence?

What if Tolkien's legendarium was his attempt to reconstruct not only the geography of prehistory, but the history of prehistory? What if Tolkien had some sort of intuition as to the truth of Europe’s pre-history and the reality of myth? Did he actually believe his stories to be based in truth? What if Tolkien possessed some sort of genetic memory, some ability to transcribe forgotten tales of lost lands and ancient heroes?

I want to take a quick pause to thank you all for reading and supporting my writing. I just passed my two-year mark of writing here on Substack, and I’m honored to have had such great support and to have attracted such an interesting community thus far.

A considerable amount of time and effort goes into these essays, so I especially appreciate those of you who support me financially as patrons- a sincere thank you! These readers support me out of pure generosity, as I don’t currently write exclusive articles for those on the paid membership tier. I think writing should be widely read and freely shared, so I don’t see the sense in locking things up behind a paywall. If you would like to help me keep things that way, consider upgrading your subscription below.

And now, back to the perilous realm…

Blood Memories, Fell and Fair

Tolkien’s stories describe a world similar to what prehistoric Europe may have really been like, ages and ages ago. Wars between lower and higher races of hominids reflected as conflicts between the orcs and the dwarves, and marriages between allied hominids like in the tale of Beren and Luthien. His tale of the sorcerer-king Sauron in Mordor mirrors tales of sorcerer kings like Nimrod in the Near East. What if Tolkien was trying to put all the pieces of European myth together into a complete whole? What if Tolkien was able to create a myth that is actually more whole, more “true”, than the scattered legends we consider “real” mythology?

Could the memories of these mythic events be seared into our psyches, or even into our DNA?

Genetic memory, sometimes referred to as “blood memory”, is a theory in psychology that posits that memories can be inherited through DNA and incorporated into the genome over a long enough span of time. Epigenetics has demonstrated that inheritable genetic differences can be acquired in one generation due to environmental conditions, i.e. changes in the life of one organism can then result in genetic differences passed down to offspring. Can the principles of epigenetics be applied to the collective unconscious? The theory that blood memory applies only to the general or common experiences of a species or tribe is more commonly accepted as plausible, whereas the theory that a specific memory can be passed down is considered more fringe.

But there have been scientific experiments testing this idea. In a 2013 study mice were trained to fear a specific smell, and they passed on their aversion to their descendants, which were fearful of the same smell, even though they themselves had never encountered the negative stimulus their ancestors had learned to associate it with.

Likewise, young chicks have also been observed to fear the shadows of birds of prey despite having never encountered one before. It’s called the “hawk/goose effect”. If this is “instinct”, then how is instinct different from genetic memory? For that matter, how do Jung’s archetypes actually differ from blood memory?

J.R.R. Tolkien himself clearly had some inklings as to the idea of blood memory. In 1964 he wrote this letter to Christopher Bretherton regarding his Atlantis-tale of Numenor:

"This legend or myth or dim memory of some ancient history has always troubled me. In sleep I had the dreadful dream of the ineluctable Wave, either coming out of the quiet sea, or coming in towering over the green inlands. It still occurs occasionally, though now exorcized by writing about it. It always ends by surrender, and I wake gasping out of deep water. I used to draw it or write bad poems about it."

It seems the professor had some connection to these lost tales beyond just an academic interest or personal appreciation. I think may Tolkien provide us with an example of someone who was somehow able to tap into a sort of “blood memory” as shown in his Atlantis dream, which he used to create archetypal stories of European prehistory that were “real” in some sense, if not in the literal details. Middle Earth is Ice Age Europe, and somehow, either through blood memory, intuition, encyclopedic knowledge of European mythology, divine inspiration, or (most likely) all of the above, the professor channeled memories of what Europe once was.

Tolkien wrote tales of an era where men interacted with other kinds of hominids, some friendly, some deadly. An age where heroic men, elves, and dwarves battled ferocious and cannibalistic orcs and goblins. But could this actually be “blood memory”? Did a world like Middle-Earth ever actually exist? It may very well have.

A book entitled Them & Us by Danny Vendramini suggests that our human fear of monsters and glowing red eyes in the dark is a genetic memory passed down from thousands of years ago, the time of an age-long war with cannibal, orc-like Neanderthals. Sounds far-fetched to you? Maybe, but this article by

(also this one by ) explains the idea and the book very well. It’s not as absurd as it may sound.Vendramini begins his hypothesis with the concept of TEEM theory or ‘Trauma Encoded Emotional Memory’ which posits that extreme stress can leave a mark on the mind and DNA of an organism, thereby enabling these experiences to be passed down as instincts to its descendants. Vendramini then speculates that there may have been a war lasting many thousands of years with the Neanderthals that explains their eventual extinction, and that the TEEM mechanism would then explain why the human phenomenon of the “uncanny valley” elicits such a feeling of dread. Perhaps we have a primal fear of a predatory race encoded into our genetics. Such a long prehistorical war could also have provided the seed for our archetypal myth concerning the rescue of maidens from sexually violent wild men, as well as providing the origin for tales of trolls, orcs, giants, and other monstrous beasts. But were Neanderthals actually monsters?

Although they stood a foot shorter than modern humans, it is already well established by anthropologists that Neanderthals were inhumanly strong, their broad frames, heavy bones, and massive trunks suggesting a natural musculature far beyond even the strongest modern humans - the typical Neanderthal could probably bench press more than the average power lifter can deadlift. They were apex predators, eating a diet of almost entirely meat, and they had enormous teeth. We know they made weapons, as we’ve found preserved Neanderthal spear tips.

Sites showing bones that had been cracked open for the marrow to be extracted are suggestive of cannibalism. Some speculate that they may have even been covered in thick fur due to originating in a cold northern climate. Neanderthals also had very large eye sockets; Vendramini points out that large eyes are indicative of a nocturnal lifestyle, and goes on to speculate that they may have had additional adaptations to low light: vertical slit pupils, which other nocturnal primates possess, as well as a reflective layer such as the cats possess. The latter may have led to their eyes glowing at night, perhaps initiating our human fear of red eyes in the dark. Putting this all together, the Neanderthals sound very much like they could have been something similar to Tolkien’s orcs.

Alternatively, if you choose to disregard theories about red eyes, fur, and cannibalism, Neanderthals still sound very much like another one of Tolkien’s races, the dwarves, which were similar in stature to orcs, lived in similar habitats, and warred with them bitterly. When you consider that there was another species very similar to the Neanderthals, the Denisovans, this becomes quite interesting. What if both dwarves and orcs really existed, and we remember them in our myths?

Whatever the truth of Vendramini’s theories on Neanderthals in Them & Us, the broader idea is hard to entirely dismiss.

Even without accepting speculations regarding (currently) unverifiable aspects of neanderthal physiology, given that paleoarchaeology and paleogenomics both attest to extensive interactions between our ancestors and other species of the genus Homo, how can the “scientifically” minded turn up their noses at the idea that myths about elves, orcs, demigods, fae, or dwarves could be based in historical fact? How can we be so sure that we never warred against something akin to Tolkien’s orcs? There must be some cognitive dissonance at work here.

We may call them Denisovans, Neanderthals, Homo erectus, Home habilis, Homo floresiensis, Cro-Magnon, and so on, but our ancestors would have called them by other names. The Latin nomenclature of scientific taxonomy is devoid of real, emotional meaning to us, and so it is allowed. But start attaching the names from myths and legends to them, and people start to get uncomfortable. But why? What is more likely? That we made up myths of encounters with other races for no reason, out of thin air? Or that those myths are based on the intertwined strands of our genetic and oral memories of prehistory? Which is really harder to believe?

And what of other types of “blood memories”, not monstrous but beautiful? TEEM theory assumes trauma, but peak, euphoric experiences also leave their mark on the human psyche.Do we also possess blood memories of the heights of human experience and achievement? Lost kingdoms, elven princesses, faerie woods, and shining citadels? Could that be why the myth of Atlantis, both our greatest achievement and our greatest tragedy, has left such a mark on us? Could it be that every culture on Earth longs for a paradise because we remember Eden, the home we lost? Do we love certain fantasy aesthetics because they remind us of past worlds inhabited by our ancestors? If blood memory is indeed a real phenomena, then we can logically conclude that the races of the world each possess a unique “racial memory” due to their differing experiences, and this could in part explain racial differences in aesthetics, morals, biases, and culture. Do we Europeans love our tales of ancient swords and chosen heroes, grim fortresses and high white towers, elven princesses and tall kings, grand adventures beyond the north wind- because the memory of those days dwells deep within us? This is speculation, but one must wonder how much the collective human experience has imprinted on us. How much do we really remember?

But can “blood memory” alone explain what is going on in the realm of myth? No one explanation seems comprehensive enough to capture what Tolkien was doing in his legends, or to explain what myth is in its entirety. I think blood memory alone can only be one piece of the entire picture, just as Jung’s “collective unconscious” was insufficient on its own to explain the recurrence of mythic archetypes. There must be an ultimate source for the unfathomably deep well we call myth.

Tapping Into the Divine Pattern

If the universe is divinely ordered, if God weaves divine patterns and stories into it, the natural conclusion is that myths are real because they are our way of remembering - and perceiving - the fundamental truths of this cosmic pattern. But in this case we are not only dealing with ‘stories’. A divinely ordered universe following a sacred pattern implies that myths are not only present in the “background” in some sort of symbolic sense (though they are there) but that they must also manifest in our actual, literal, material world. The material world follows the cosmic pattern, just as psychology follows the pattern, and just as our legends and folklore follow the pattern. It becomes a chicken-and-egg question to ask whether history, folklore, or human consciousness came first. If the events of human history are influenced and even created by these overarching divine patterns, then the Jungian archetypes that dwell deep in our subconscious must be made out of the individual moments of human history. “As above, so below”.

I think to understand this idea of “tapping in” to God’s divine patterns, we have to understand the symbolism of the Divine Mountain. In Christian symbology, all things, all realms of existence, move up towards the highest thing, that is, the one true God. Along the journey up the mountain you may pass through many dimensions that reflect divinity in different ways. But the ultimate Truth at the top of the symbolic mountain is the same truth you find at the bottom (or in the material world). The patterns of reality are fractal. So, a simple farm boy venturing into a dark forest to find a lost sheep, and Christ Himself descending into Hades to free humanity from the clutches of death, they are both following exactly the same pattern, the same reality, at two very different levels of manifestation.

And so I wonder if certain people - artists, prophets, oracles, sibyls - are able to “tap into the pattern” in some literal sense. Many artists tell similar stories of how their greatest works came to them in a dream or vision, such as Tolkien’s dream of the deluge that sank Atlantis. We can come back to Jung here. What if his later, more mature view, that there was more to myth and symbol than hallucinatory psychological phenomena, was correct? What if his archetypes exist as literal, fundamental divine realities that manifest themselves in the cosmos in an endless number of ways? As history, as prophecy, as psychology, as literature, as symbology. What if Jung’s spiritual experiences with the archetypes were his own experience with “tapping in” to the divine patterns?

Are some of the writers of what we consider “fantasy” and “sci-fi” some sort of modern day augurs, acting as conduits for the collective unconscious - not simple story-tellers, but blood remembrancers? Tolkien certainly appears to have been some sort of conduit for long-forgotten tales of Europe’s pre-history. What about others, like Homer? Is the Iliad truer than scholars give it credit for? Perhaps some are able to tap into the “pattern” of reality and extract these old and forgotten stories from it. This idea of tapping into a divine consciousness and receiving revelation is certainly one found in all kinds of traditions.

It could be that the explosion in the “fantasy” genre’s popularity has been precisely because the modern West lost touch with its native mythologies, and with the memory of the deeds of its ancestors. The popularity of “fantasy” could be an expression of these blood memories coming to the surface, memories of an ancient mythical Europe - a cold, icy age full of exotic races, dragons, and heroic quests across treacherous mountain ranges and dark forests. Perhaps we have an inherent need to tell the ancient stories of our ancestors, and will find a way to do so even if we lose touch with myth and folklore. Perhaps after we stopped believing in our ancient myths and legends, after hundreds of years something in the memory of our DNA needed to be expressed. Something dormant had to spring forth. This is where the idea of blood memory meets Jung’s theories on the collective unconscious. Perhaps our collective unconscious can decide when a story or an archetype from our forgotten past has slept too long.

And if some stories are based in “blood memory”, what if others are prophetic? Perhaps some storytellers can tap not only into memory, but visions of what could be our future. What if Star Wars is not a tale of a long, long, time ago, but actually of a long, long, time in the future. Or, what if it's both? The cycles of myth go round and round and round.

This all makes me wonder: if our myths were completely forgotten, would they reappear anyway due to remaining in our collective blood memory (or our “collective unconscious”)? If an apocalypse were to totally wipe out our recollection of myth, legend, and religion, would the great tales of the past eventually reappear in our stories through some extraordinary man’s connection to divine realities?

Just as our past was molded by the mythic patterns, so must be our present and our future. The myths are ongoing, as the “pattern” will continue to manifest itself as long as the cosmos exists. Myths are happening among us, our current events are just as mythic as the past.

The patterns of our current-year world politics and culture are following the mythic patterns - we are still living in the Great Tale. Against the modern world’s background of banality, we are seeing a rise of fanatical cults practicing dark rituals. The ethno-religious conflict playing out in Palestine, or the rise of “woke” cannot be described as anything but mythic in nature. The tale of how the entire world shut down and vehemently persecuted all naysayers during 2020 would fit into any folktale compilation.

We see little myths and folk-tales pop up all the time. Take the red-haired brother tale for example, like in the story of Jacob and Esau. The red-headed brother or stepchild in folklore represents wild nature, the black sheep, the outcast, etc. You may never think much of this, but you can look at the lives of Princes Harry and William of England and witness it. It's disconcerting to see how the story of the modern Royal Family is following this ancient pattern, as Prince Harry has become the black sheep and outcast. Of course, it’s only disconcerting if you don’t expect reality to follow the mythic patterns in the first place. If you do, it’s nothing out of the ordinary at all.

And our future may become more mythic still.

had a great piece where he explores how our culture’s transhumanist-nihilist experiment may be reverse-engineering orcs and other monsters as we speak. I believe we may see an age where the “dam bursts” so to speak, where we live again in an age full of mythic events, symbolism made real, an age where magic comes again to the forefront. We may indeed live to see horrors, but also beauties, far beyond our comprehension. Our story is not over, and all of history will follow God’s order and the divine patterns until the end of the ages.The Cauldron of Reality

At last, we come back to the stories themselves.

We’ve examined how the Divine Pattern of the Cosmos manifests itself in our collective unconscious, in our literal history as well as current events, and in the minds’ of artists and prophets, who turn ancient memory and divine truth into myth and legend. Our favorite tales, passed down from time immemorial. But once created, what is the actual role of these mysterious tales in our lives?

In his famous essay On Fairy Stories, Tolkien called myth the “Cauldron of Story”, by which he meant that myth is like a great pot where all manner of things both high and low are thrown in and mixed together: historical figures, archetypes, the natural world, gods and goddesses, etc. From this cauldron comes our myths, legends, fables, and faerie-stories. But while Tolkien’s metaphor is vivid and surely correct, perhaps it does not go far enough. Perhaps it may be better to rename myth the “Cauldron of Reality”. For myths are not just stories, they are what we use to make sense of the entire cosmos. You could even go so far as to say that myth contains the cosmos. We use it to condense immeasurably deep truths that are otherwise impossible to describe. We return to myths again and again because they are true, not only symbolically or metaphorically, but in every possible sense of the word. The myths are the realest things we possess, each one filled with infinite layers of truths waiting to be revealed. They are a part of us, just as we are a part of them. We, created beings within the divine order pattern, have an innate desire to act out that pattern ourselves. We, the created, are sub-creators. The myths make us, and we make the myths.

The myths may be recollections of the past, and visions of the future, and representations of archetypal truths and symbols that dwell deep within our subconscious - but they are our present too, our guidebook to life. They point the way. Myth is the Great Tale, the Cosmogonic Round, the Cauldron of Reality, the archetypal story that plays on and on and on, forever. The great tales never end, the board is merely reset, and a new cast called up to play them out.

If we understand myth in this manner, arguing over which interpretation of myth is “correct” misses the point. Are the tales of King Arthur and the search for the Holy Grail historical stories of a real iron-age warlord and his court? Alchemical symbology? A religious metaphor for the journey of the soul? Something springing forth from the collective unconscious? Tales for conveying wisdom and life-lessons? The answer is, of course, “yes”. The stories of Arthur and the Grail are all of those things, and much more. The Arthurian saga was created as countless elements churned together over time in the realm of myth, in the Cauldron of Reality, until they emerged as a primordial tale, a true myth.

A fundamental reality can be understood in many, perhaps limitless ways. What is the myth of the serpent? A blood memory of battling reptiles, or even dragons or dinosaurs in the prehistoric jungles? A memory of the long-tailed comets that brought devastation on the ancient world? A symbol of deception? A metaphor for chaos? The devil himself, the serpent who tempted Eve in the garden? It is all of these things. The serpent is a primordial reality that manifests in countless lesser realities.

Myths are also used by human cultures as a way to contain the infinite truths and patterns of the cosmos inside of digestible stories. In this way, myths play a similar role to folk-wisdom sayings. You may not be able to teach an average man much about philosophy, human relations, or the finer points of theology, but you can teach him proverbs. “Do under others as you would have them do to you”, “a penny saved is a penny earned”, “don’t put all your eggs in one basket”. Through these sayings, deeper fundamental wisdom can be passed down to future generations. We use myths in the same way. Folktales carry wisdom, and can teach us more about life than just about anything else. We can learn from Snow White, from the frog-prince, from the emperor with no clothes. Mythology is like an onion that contains never-ending layers of truth within it. As C.S. Lewis put it, you can go “further up and further in”, forever. In peeling the layers back, we reveal not the one truth behind reality, but reality in all its infinite, multifarious aspects; but in the simple telling and receiving of the myth, we can touch reality in its mysterious and implicit whole. Like receiving Christ in the Eucharist, it is a mystery beyond comprehension. Using myth, we are able to describe the indescribable, and we find that the entire cosmos can be fit into a child’s bedtime story.

It is therefore only natural that myths function as the basis for our modern storytelling. We connect to stories that are true, stories that tap into the divine pattern. This is why many modern stories fail to connect with audiences. Modern studios are attempting to sell us stories that we instinctively recognize as fundamentally untrue. Most people are unable to articulate exactly why something like Amazon’s The Rings of Power is so offensive, and they usually settle on something like “it disrespected Tolkien’s lore”. But what they’re really offended by is its total disregard for the spirit of the work, the underlying truths - that is, the dismissal of the divine pattern in favor of a merely human ideology … an ideology which, because it ignores the divine patterns, is necessarily infernal. Disney’s Marvel Cinematic Universe is an interesting case, because they have both followed traditional mythic story structures and disposed of them. The earlier MCU films that followed mythic story patterns were big hits, the downfall of Marvel occurred when they stopped following this structure. They were usually accused of going “woke”, which was true, but the real problem originated at a deeper stratum. They stopped telling “mythic” stories, and so their stories became untrue, and therefore distasteful.

Modern works disgust us when they try to create their own reality rather than tap into the fundamental truths. We saw the same thing with the ending of HBO’s Game of Thrones. The ending didn't just fall flat because it was executed poorly, it fell flat because the characters did things that were offensive to the patterns of truth, of actual myth, which the writers then tried to play it off as “subverting expectations”. It didn’t work. Stories that are loved are loved because they are fundamentally true tales.

And perhaps the great myths have yet another purpose. We’ve explored how the Divine mythic patterns shape reality, but do mythological stories themselves play a role in bringing those realities about? What if the recollection of the archetypal patterns and histories is meant to regenerate and realize those patterns in the present? What if retelling these stories again and again allows the divine pattern to influence our psyches on both individual and collective levels, priming us to take on mythic roles in our own lives? If the world is in need of a dragon-slayer, perhaps myths are able to influence the psyche of a candidate until he is literally fit to become one.

We often say that heroes arise seemingly at random from the most unlikely places, but what if it is less random than we think? What if the farm boys and orphans that rise to heroism were being primed by the divine patterns from the beginning? What if they were the children with an innate fascination with the myths, with stories of past heroes and adventures, and what if these stories then influenced their subconsciousness to the point that they were actually made into the archetype that they dreamt about, ready to take on whatever dragon, real or figurative, was plaguing their world?

What if the reason that we have “blood memories” of mythic events is because the men and women living in those ancient days already had their own mythic tales, tales that were priming them to live out their lives and carry out the great deeds that have been passed down to us as new myths? What came first, the myth inspired by the hero, or the hero inspired by the myth? Do we repeat the stories of the past without end?

This should be a comforting thought: that no matter how bleak things may become, and no matter how far Man may fall into darkness and despair (and fall we will), the divine pattern goes on, and the myths will not die. No tyrant, no new world order, no governing body can do anything to change this. The flame may flicker, but it will not die. There will always be a seed ready to take root, even amidst the darkest of times.

And some little boy somewhere, unprompted, will take up a stick from the street, and something inside of him will know that it is a sword fit for slaying dragons. And years later, when that little boy is grown, he may find his true sword, and look the dragon of his day dead in the eye. And so long as he does, the great tales will never end.

I hope you found this journey into the realm of myth edifying. A natural question at the end of an essay like this may be, “Ok, what do I do with this information? What is the point?”. I ponder the same things. In fact, it was writing this essay that inspired my new series, "Defeating Disenchantment". In it I’m attempting to examine what has been called the “dis-enchantment” of the modern world, and searching for the means by which we may “re-enchant” both creation and ourselves.

This essay was originally published at Postcards From Barsoom. I must express my appreciation to my friend

, not only for publishing the essay, but for offering up precious hours of his time in helping me develop my thoughts, and most generously for putting the essay through multiple rounds of (much needed) editing. I’m quite proud of our final product. Thank you, John. You can explore John’s fascinating writing at the link below:

Great stuff, thanks, and particularly interesting re: the possibility of Tolkien possessing preternatural knowledge of Ice Age geographies etc.

Lucien Lévy-Bruhl posits a theory of myth: that early humans believed themselves surrounded by a supernatural realm; thus, myth was not the product of reason and logic as we might suppose, but by mystical participation with genuine, directly apprehended powers. Therefore, man engaged with Nature in a state of transcendence, and myths were the products of those unmediated revelations of gods and goddesses.

In other words, humans once existed in a state of enchantment and, as such, were able to perceive the otherworld, with which they co-existed. The long process of disenchantment has cut that faculty out of human consciousness, possibly in a way similar to epigenetics: over the generations, our ancestors have seen an increasingly materialistic worldview - reinforced over and over - written into their DNA. Therefore, one challenge of re-enchantment is to undo the ancestral 'curses' that deny us an enchanted existence.

I could add that one such ancestral curse denying our ability to attain an enchanted relationship with Nature is original sin, but I guess that might be construed as unfair ;-)

Beautifully written, I've been thinking a lot about 'blood memory' for a while now. Often in regards to Neanderthals being our real version of dwarves (short, stout, barrel-chested) and the Cro Magnons being the real version of elves (tall, strong, highly intelligent, etc). In addition, I've often thought that our myths of dragons are directly linked to dinosaurs who terrorised the world for our mammalian ancestors back in prehistory. Maybe that's a stretch though.

Anyway, I've rambled enough. That was a fantastic essay and I can only hope that you keep writing such great works.