Rockall: The Ruin of Beleriand, Hy Brasil, and the Grave of Turin Turambar

The Lost History of Middle-Earth, Part 3

"And some things that should not have been forgotten were lost. History became legend. Legend became myth."

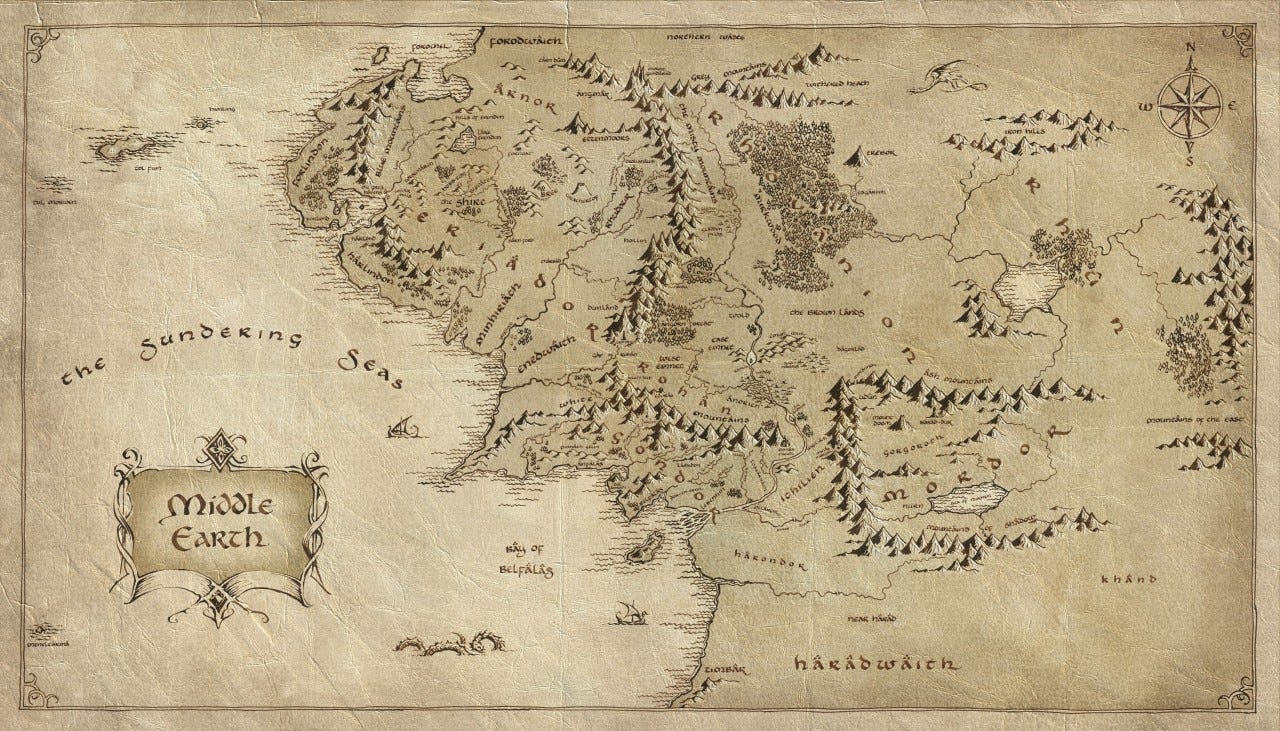

It was back in December of last year that I was once again playing around with the idea that Tolkien’s stories are literally meant to take place in our ancient past, specially in Ice-Age Europe, and not just in a frame narrative sense.

I just had just re-read The Silmarillion and was scouring through it looking for more hints from Tolkien as to the real world locations of lands or landmarks of Beleriand.

And as I read, I came across this.

Of the isle of Tol Morwen, the final resting place of the hero Turin Turambar, and the location of the Stone of the Hapless, Tolkien writes this:

"It is told that a seer and harp-player of Brethil named Glirhuin made a song, saying that the Stone of the Hapless should not be defiled by Morgoth nor ever thrown down, not though the sea should drown all the land; as after indeed befell, and still Tol Morwen stands alone in the water beyond the new coasts that were made in the days of the wrath of the Valar".

Now, I had never even realized that in Middle-Earth there was a third island-remnant of Beleriand in addition to the larger two islands more normally seen on maps.

But this seemed an obvious hint that we should still be able to locate Tol Morwen in our modern day… assuming I was correct that the Professor was intentionally making these references to our real world and that Middle-Earth is literally just our own world in the ancient past.

Looking at my maps from my previous posts, it appears clear that Tol Fuin is Iceland, and Tol Himling is Faroe. But this isn’t really my idea, this connection has been made plenty of times and is fairly obvious based on the shapes of the islands. I believe that other Tolkien fans have at least noticed the similarity to Iceland and Faroe before, even if they thought it was only somewhat a reference and not meant to be literal.

But little Tol Morwen almost never appears on Middle-Earth maps, and I had never even heard it mentioned, and certainly I had never heard it connected to anywhere in the real world.

But Tolkien’s quote seemed to imply that, if my theories correct, I should be able to locate Tol Morwen in our modern day.

This seemed to be the perfect test of my whole theory. If the island turned out to be there, it would vindicate me and prove that Tolkien was doing exactly what I’ve been saying he was. But if the island wasn’t there, I’d have to disavow my articles in defeat, or at least, soften my claims.

Fantastic stakes.

With this in mind, I was set on trying to find this mysterious, third island that according to Tolkien would “never be thrown down”.

There HAD to be a small island south of Iceland and Faroe that generally lined up with where Tol Morwen should be.

But there was a problem. If you’re familiar with maps of the Atlantic, you know there isn’t much there besides Iceland and Faroe. It’s rather empty.

But, confident that Tolkien would come through for me, I spent the better part of an hour or more scouring the Atlantic in Apple Maps.

I found nothing.

Despairing, I eventually turned to Google search.

“What islands are there in the North Atlantic?”

Well, besides Iceland and Faroe… it turns out there is one. Almost invisible.

A lonely outcrop of rock in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean that holds the title of the smallest territorial claim of the British Empire.

A gloomy, isolated, wave-battered island, inhabited only by the seabirds.

Rockall.

You can watch a short documentary on Rockall’s fascinating history here.

I almost couldn’t believe my eyes, but at the same time, I had hardly doubted that I would find it.

Here it was. A solitary, tiny island, almost exactly where I had been looking for it. In fact I must have passed over it during my search, but to even see it on maps you have to zoom in to highest possible setting and even then, Rockall is barely visible.

Now, if you compare the real-world map to the map of the islands of Beleriand, you may notice that Tol Morwen is more under the left side of Tol Fuin/Iceland, whereas Rockall is more under the right side. Frankly, I don’t feel the need to be quite that exact- for our purposes, this is more or less a direct hit.

And for me, this is conclusive evidence that I’ve been on the right trail with this whole series. By trusting just one small hint in Tolkien’s writing, I was able to find the exact place he spoke of.

And if finding an island almost exactly where Tolkien said we would isn’t uncanny enough, the resemblance between Rockall and artistic representations of Tol Morwen is almost exact:

So of course, next I had to find out whether Rockall has any connections to any sort of folktale or legend possibly related to Tolkien.

Turns out, it does.

In an online PDF of info about Rockall, I found this from author Ondřej Daněk Gymnázium:

“According to the mythology, Rockall is the only remnant of the Kingdom of Brazil (not to be confused by the current state), which was a Gaelic Western land of the eternal youth. In some maps (of 16th and 17th century) there is noted a phantom island of Brazil, and thus it is possible, that these two islands are originally the same in the mythology (i.e. this myths attributes the features of Brazil to Rockall). In fact, no island like that does exist. It can be supposed that rather this phantom island was influenced by the myths and ‘unclear existence’ of any islet in these parts of the Atlantic (i.e. by the existence of Rockall). On many maps from this period there are noted many other phantom islands (as Buss, Verde, or St. Brandan’s Island and many others) in that area. According to the Irish mythology, Rockall originated as follows: One of the national heroes, Fionn mac Cumhaill, grabbed a piece of the ground and threw it against the enemy. But he missed and the clump became the Isle of Man and the pebble became Rockall. In the Scottish (Gaelic) mythology Rockabarraigh figures as a mythical rock, which is supposed to appear only three times, lastly at the end of the times: When Rockabarraigh returns, the world will likely be destroyed. The name Rockabarraigh does not need to mean Rockall, but it is probable that it originated from any unclear information about Rockall."

Now, Tolkien was always fascinated by legends of lost Faerie islands and enchanted lands to the West, specifically the legends of the phantom island of Hy Brasil. He actually mentions the mythical island in his essay On Fairy Stories.

It would not surprise me at all if he secretly found a way to work the island into his own myths in this way.

More than that- Tol Morwen/Rockall is not just a remnant of Beleriand, but specifically its the remnant of the forest kingdom of Doriath- that is, the enchanted Elven kingdom of Beleriand. This lines up perfectly with Rockall’s possible connection to Hy Brasil, which as I said, Tolkien likely knew of. But Rockall, which is possibly Hy Brasil, lining up with Tolkien’s own enchanted Faerie kingdom is too strong a coincidence to actually be one.

In fact, it may even be possible that this connection is what inspired the legends of Doriath in the first place, rather than just being an Easter egg or an afterthought.

Does this mean it may be possible that rather than being a footnote, the island of Rockall and the story of Turin and Tol Morwen was actually the origin of the Beleriand legends, and that Tolkien centered his First-Age myths around it?

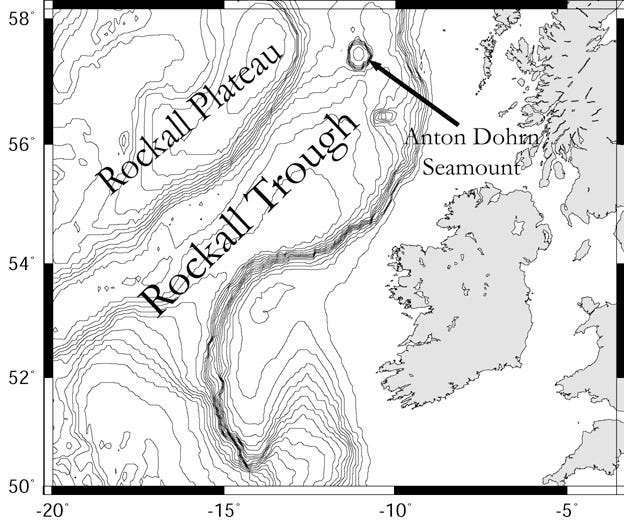

I find it very likely- Because Rockall is not just a lone island, but is actually the last standing part of an entire subcontinent1- Rockall Basin.

This interesting geological formation just happens to be where Beleriand would have sank beneath the waves, lying immediately to the west of the British Isles, south of Iceland and Faroe, exactly where Beleriand should be.

You can clearly see the outline of it on any online map. Just go look at it- it immediately screams “Beleriand”.

My gut tells me that Tolkien knew about this underwater basin as well as Rockall island, and that it must have been part of the early inspiration for his Silmarillion legend that he began as a 19 year old.

It makes sense- combine his love for legends like that of Hy Brasil/Rockall with his love of the Norse world sagas of Iceland (and Faroe), and then imagine he learned that these islands were connected by an underwater landscape that may once have stood above the waves.

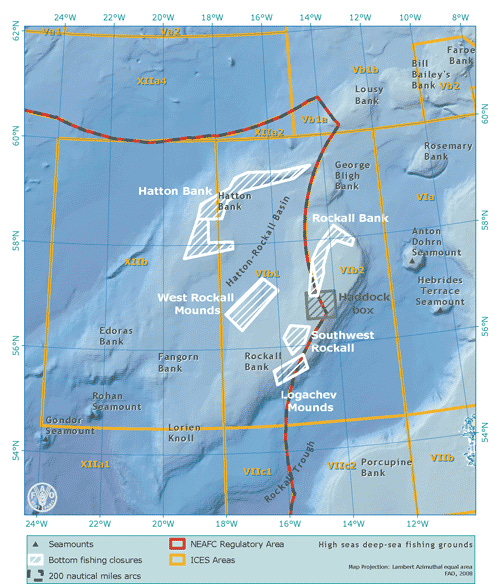

And the connections go further than that- inexplicably, features of the Basin are named after locations in Tolkien’s Middle-Earth- Edoras Bank, Lorien Knoll, Gondor Seamount, etc. Now, none of the names are Silmarillion names, but the connection is just too odd to be completely coincidental.

The Basin features were named through this organization.

But who submitted the names? Who made this small connection, and when?

Well, whoever they were they apparently weren’t the only one.

Geologist William Sarjeant's fantasy series “The Perilous Quest for Lyonesse” was inspired by The Lord of the Rings and is actually set in the mythical land of "Rockall", which he based on Rockall island. What’s more, some of the features of the Rockall Plateau have also been named after Sarjeant's books. Did Sarjeant really make the Rockall-Beleriand connection, or was it a coincidence? I don’t think it reasonably can be.

Moreover, Sarjeant was a geologist and a professor- was he actually the one who christened the Middle-Earth named features of the Rockall Basin? I couldn’t find anymore information on it to say one way or another.

All things considered, I think it’s undeniable that Tolkien based Beleriand and the island of Tol Morwen on Rockall, and I believe that this tiny island may prove my theories more conclusively than anything else thus far.

This tiny island, the grave of one of Tolkien’s most tragic heroes, could possibly be one of, if not the initial, origin points for the entire saga of Middle-Earth.

Now when I read these words, "the Stone of the Hapless should not be defiled by Morgoth nor ever thrown down, not though the sea should drown all the land; as after indeed befell, and still Tol Morwen stands alone in the water beyond the new coasts that were made in the days of the wrath of the Valar", I cannot imagine that they refer to anything but the lone isle of Rockall.

And as far as I can tell, I’m the only one who has ever made this connection.

Well… almost the only one.

During my caffeine and blood memory induced quest through the dark forest that night in December, I spent hours combing the internet for references connecting Rockall to Tol Morwen or to Beleriand in general, trying to figure out if I really was the first person to discover this.

It turns out, I am not.

I found exactly ONE other reference on the entire internet to Rockall being the isle of Tol Morwen.

In a Google chat room from 2003

See Linards Ticmanis' seemingly in-jest comment: "So when will you dig up Túrin's grave on Rockall island?"

And.. that was it. No further or previous reference to it in the chat, nothing in Linards’ post history either. That was it.

I tried emailing Mr. Ticmanis to no avail. It appears that he is possibly Danish. And possibly a computer scientist.

But here, in the deepest depths of the early 2000’s internet, is where this trail finally went cold, and where I put the tale of Turin’s final resting place to rest.

Linards Ticmanis, if you’re out there- this essay is dedicated to you.

This may be the wrong terminology, but I’m no geologist.

Dear Andrew,

Firstly, many thanks for continuing to write about and investigate your interpretation of Middle Earth's geography. Also, please forgive the epistolary form of this comment; this is how I write. Tolkien probably had a hand in this, as did Michael Moorcock and so many other fantasists. We are all, after all, part of the same tapestry of thought, for all that it is unravelling. Also: I work in videogames, and I've been honoured to encounter some of the great fantasist writers as a result. Therefore, please also forgive any name dropping. As blessed as I have been with these encounters, it is a small curse to be disliked for talking about it.

I worked on a videogame series known as Heretic Kingdoms, which has been an adventure, and last year somebody in Eastern Europe wrote to me in order to ask whether I was a scholar of Eastern European history from the fall of Roam to the Middle Ages, because he could relate my fictional history of the Heretic Kingdoms to actual events in the region. Reading everything he had put together was dazzling. But of course, I am a Brit and entirely ignorant of the history around the base of the Ural mountains. Then again, it's not that I'm not well-read. Even if his detailed mappings of my fictional timeline onto his historical one were beyond possibility, the confluence of influence could still remain. I wish we had a word for this kind of synchronicity that would not reduce it to coincidence, as it is a deeply meaningful force in thought.

Conversely, you sometimes write as if you can prove your vision of Tolkien's motives by gathering evidence, as if what you were doing were a scientific investigation. But it isn't. It's a historical investigation. We have forgotten, almost entirely, a lesson I learned from my philosophy mentor, the dear departed Mary Midgley: that the sciences are not the only means of uncovering or assembling truths, and that there are other methods that are not only valid, but actually better suited to some of the tasks we face. I write this point not as a criticism of what you are doing (which I love) but as a general criticism of our time. This process of uncovering connections is invaluable whether or not there is any question of 'proof', which is something I have learned through my own pursuit of similar conceptual excavations (e.g. connecting the Grand Theft Auto games to Elite, which I have 'proven', and to Paradroid, which I probably never win). Even if you had not discovered Rockall, your process of investigation would still have had merit, and still have been worth writing about. I hope that if you had not found it, you would still have shared your thoughts about it.

Now for what little it's worth, I always thought that Middle Earth was supposed to be our world in the distant past, and this for several reasons. Firstly, and most importantly, the arrogance of my youth when I would leap to a conclusion first and ask questions later. Secondly, the actual text of The Hobbit, which directly tells us that the world of the mid-twentieth century is ages after Bilbo's adventures, and that goblins are responsible for the most diabolical of our weapons and that golf was invented by a hobbit. I always thought (ignorant as I was of 'Midgard' at the time) that 'Middle Earth' meant 'the Earth between the lost Golden Age of the past and the future time of now This is clearly a mistake. But that thought was always embedded in me.

It perhaps goes without saying that the fantasy genre as it emerged in the twentieth century was steeped in the idea of fantasy realms not being 'other dimensions', as we have it now, but earlier ages of our own planet. I recently worked on a Robert E. Howard game, which alas was cancelled, but thoughts about his work are fresh on my mind. Howard of course was a key golden age fantasy writer and part of H.P. Lovecraft's writing circle. He expressly tells us the Hyborean Age where the Conan stories are set is in our past, and there are many other short stories he wrote that set up these kinds of 'lost ages' - to the extent that up until Michael Moorcock and Roger Zelazny reframed fantasy worlds as 'other dimensions', the 'lost age' conceit was the norm. Surely Tolkien must either have encountered this from the early twentieth century fantasists or else was steeped in the same literary forces that made this the default understanding of both high fantasy and sword and sorcery.

Moorcock, whom I got to know as well as any fan can know their idols while working on one of my philosophy books inspired by his work, seems also to have had a similar drive, even as he invents the literary multiverse that gave birth to the physicist's hypothetical multiverse. At the end of the Elric saga, when the White Wolf blows the horn of fate, the lands of the Young Kingdoms shift and are reformed. Moorcock never says if Europe is the geography that follows, and I never thought to ask him alas, but I think it interesting that a British writer (even one grumpy at Tolkien for reasons that amount to London vs Home Counties) who helped shift us from 'lost ages' to 'other dimensions' was still steeped in that very same literary tradition. (Zelazny, as a US citizen, had no such historical formation to draw against).

Lastly, I worked on the Discworld games where I had the honour and privilege of getting to spend time with the late Terry Pratchett. We enjoyed talking about other fantasists together, the few times we were in the same time and space (mostly press junkets promoting the games), and we discussed Moorcock's dislike of Tolkien the first time we met. Pratchett told me (and I don't know if this has come out elsewhere) that he wanted to become a fantasy writer after writing to Tolkien and getting a reply. It was a life changing event for him. Tolkien wrote back to every fan, and Pratchett committed to do the same. This means, I presume, that there is a huge undiscovered world of Tolkien epistles to be discovered. Just imagine what treasures might lurk out there, like those lost recordings of Patrick Troughton Doctor Who that occasionally appear and rock fans worlds!

I hope these thoughts are welcome, and please accept my grateful thanks for sharing yours.

With unlimited love,

Chris.

PS: I am a US immigrant these days, but over in my home land for the Summer, back in Manchester where I have lived most of my adult life. I have several times balked at writing to you about the protests and the riots, which you mentioned recently. I may yet. What stops me is the fear that we will not end up talking together about it. That's fine. It just gives me pause. I write comments online as if they were letters because nobody will write letters any more. But for me, like Pratchett and Tolkien, the letter was a sacred trust. I feel duty bound to continue writing in the form. Many thanks for your patience in reading this one.

Must find Ticmanis