“Still, I wonder if we shall ever be put into songs or tales. We're in one, of course, but I mean: put into words, you know, told by the fireside, or read out of a great big book with red and black letters, years and years afterwards." - Sam Gamgee

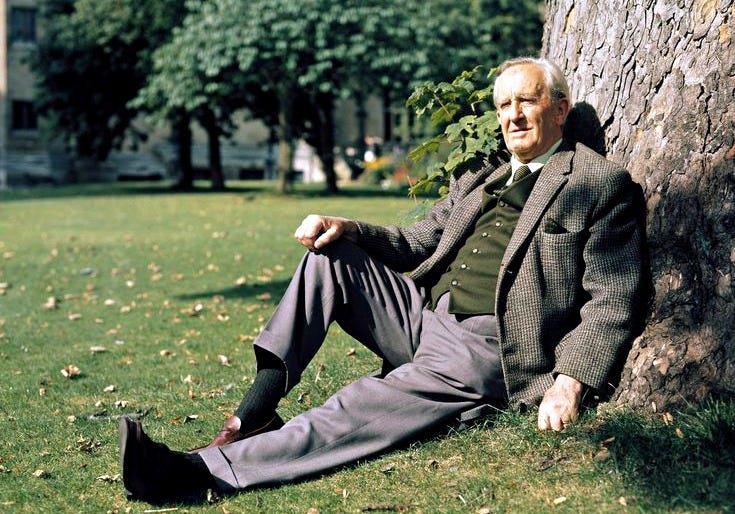

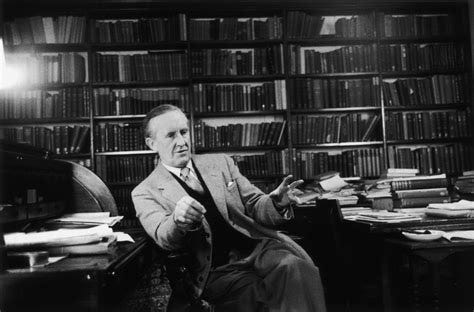

In his lecture Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics, J.R.R. Tolkien said:

It [Beowulf] is in fact written in a language that after many centuries has still essential kinship with our own, it was made in this land, and moves in our northern world beneath our northern sky, and for those who are native to that tongue and land, it must ever call with a profound appeal…

If this is true of Beowulf, an Anglo-Saxon poem many centuries removed from the modern English-speaking world, I think it is even more true of Tolkien’s own work.

There is nothing today that defines the English and the broader Western cultural mythos as strongly as Tolkien’s legendarium. No other writer has contributed so much new life to the Western canon and cultural spirit in recent centuries.

Tolkien’s works will likely be remembered as the most impactful body of literature of the 20th century. Not just fantasy, but literature. The Professor’s importance as a myth-maker cannot be overstated. Tolkien exists somewhere in the grey, not quite belonging anywhere in the library. But every year Middle Earth becomes more real, and its tales and heroes become more akin to those of Asgard than those of fiction.

Which is why it is high time the copyright to his legendarium expires and Middle-Earth is set free to the public, to the whims of any talented artist, screen producer, composer, musician, poet, or novelist that wishes to make their own adventure into Middle-Earth.

There could be no better fate for Tolkien’s works than for them to finally be released into the great public melting pot of myth and story.

But now that I’ve made all of the Tolkien fans upset, I have to explain myself.

There are two camps on the issue of Tolkien adaptions.

There are those within the Tolkien estate that allowed Amazon’s Rings of Power to be produced. This camp has no intention of allowing Tolkien’s work to enter the public domain, but they are willing to allow large studios to make adaptions.

On the other hand, Tolkien’s conservative-leaning fanbase tends to believe that the Professor’s works should be religiously guarded. They dogmatically hold that The Silmarillion and other works must be kept out of the hands of movie studios, and many even argue that allowing the Peter Jackson films to be made was a step too far. Tolkien’s son Christopher is well known for holding this view and considered reproductions of his father’s mythos as inadequate at best and sacrilegious at worst.

However, both of these camps miss what the Professor would have wanted.

Despite the disaster of The Rings of Power, I support allowing it and other adaptions to be made. In fact, not only am I in favor of allowing movie adaptions of Tolkien’s works to be made, I would even be in support of other authors publishing books set in Middle-Earth.

Allowing Tolkien’s stories to enter the public domain once the current copyright expires would be the best thing for the professor’s legacy. Not only that, but it is what Tolkien would want.

Why? Well, that requires answering a few questions.

Firstly, what were the views of J.R.R. Tolkien himself regarding adaptions of his works?

Secondly, what was his intention in creating the legends of Middle-Earth?

And finally, how can we best honor these intentions?

The first point I should address is whether or not the professor would have been in favor of adaptions of his works.

Some may be surprised to hear that Professor Tolkien’s attitude towards adaption was never quite the same as that of his son Christopher or of his most passionate fans.

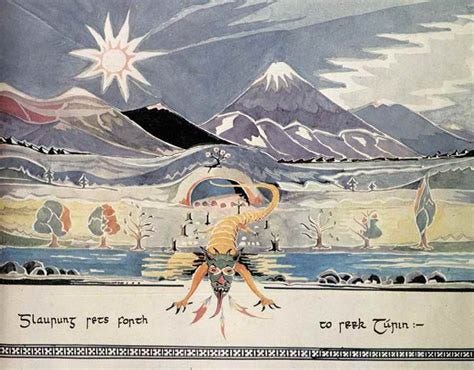

In a 1951 letter to publisher Milton Waldman, Tolkien wrote about his intentions to create a "body of more or less connected legend," of which "the cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama”.

Clearly, these are not the words of a man that wanted to keep his works far from the hands of other creative minds.

It was only specific types of adaption that he was opposed to. He rejected certain movie proposals based on his books (like the infamous Beatles film proposal) because he felt they missed the point and spirit of his work- not because he was opposed to Middle-Earth adaptions in general.

But if this was Tolkien’s opinion, why do so many of his fans take a different approach?

For the most part, its because the fans take more after Tolkien’s son Christopher, they are fans who view the Middle-Earth legendarium as something sacred that must be protected. And I should say that Christopher did exactly what he needed to do for the job he had been given and the role he had to play, in his own time. His father’s work had to be protected in order for its legacy to be cemented.

But that era is over now. Tolkien’s works don’t need protecting anymore, and especially not if they are released into the public domain- becoming part of the public domain is actually the best protection any story can get. Once mythologized, a tale is invincible. Does a bad Trojan war film diminish Homer? Do viking LARPers diminish the sagas of the Northmen? No, not in the slightest. The tales transcends any one adaption, even a terrible one like The Rings of Power.

But that word “mythologized” brings us to the bigger question- what was Tolkien’s intention in creating his legendarium anyway?

His intent was not just to write a great novel, or to create a frame narrative for his fictional languages as some have said.

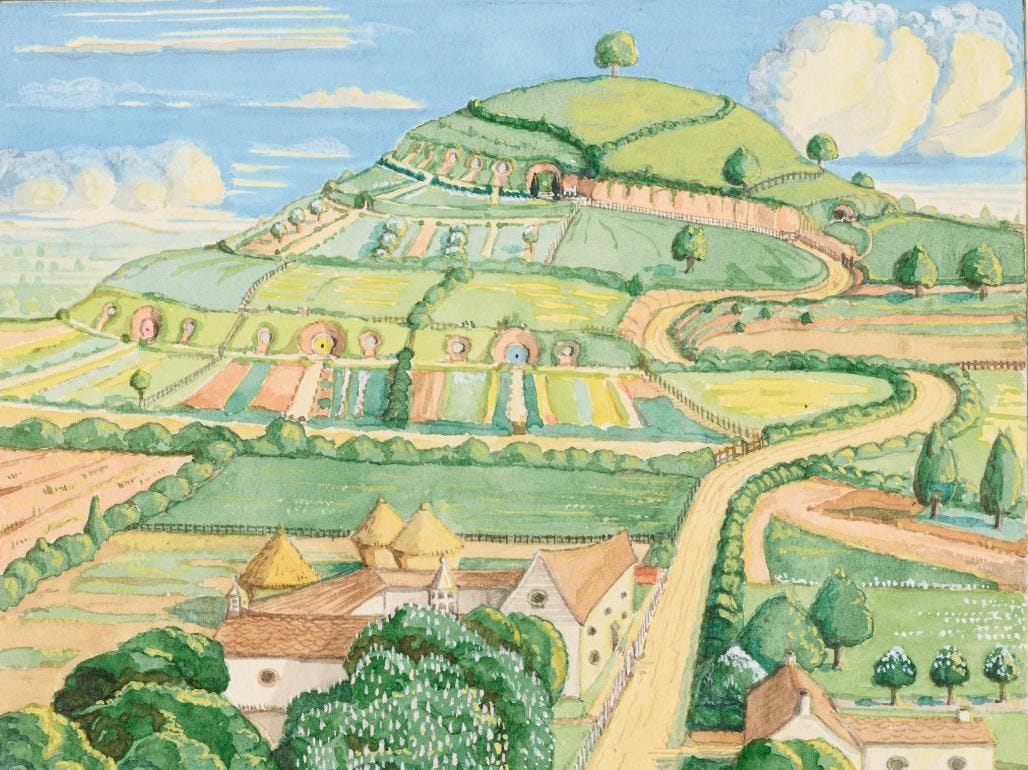

Tolkien’s intention was to write a myth. Creating the mythology of Middle-Earth was his life’s work, and he always asserted that it was meant to be a mythic history of our own Earth, not merely a work of fiction. He expressed disdain for fantasy that seemed random or was allegorical, that made no attempt to recreate the spirit that he found in real ancient myths and legends.

And when something is truly mythic, rather than just a good story, it has the potential become something more.

In his famous essay “On Fairy-Stories”, Tolkien describes the process of how stories are thrown in the “cauldron” of myth and transformed:

“speaking of the history of stories and especially of fairy-stories we may say that the Pot of Soup, the Cauldron of Story, has always been boiling, and to it have continually been added new bits, dainty and undainty… …new bits added to the stock. A considerable honour, for in that soup were many things older, more potent, more beautiful, comic, or terrible than they were in themselves (considered simply as figures of history… …It seems fairly plain that Arthur, once historical (but perhaps as such not of great importance), was also put into the Pot. There he was boiled for a long time, together with many other older figures and devices, of mythology and Faerie, and even some other stray bones of history (such as Alfred's defence against the Danes), until he emerged as a King of Faerie. The situation is similar in the great Northern “Arthurian” court of the Shield-Kings of Denmark, the Scyldingas of ancient English tradition. King Hrothgar and his family have many manifest marks of true history, far more than Arthur; yet even in the older (English) accounts of them they are associated with many figures and events of fairy-story: they have been in the Pot.”

If this is true, and if it’s true that Tolkien wanted to write a true myth- then by definition he would want that myth to be eventually added into the “pot”. Of course, Tolkien was far too humble to assert that his story deserved this honor, but this is not for authors to decide for themselves. Rather, it is up to us, over the course of generations, to decide what gets thrown into the pot.

The final and best way to honor a myth-maker is to allow his works to become myth. This cannot happen while a body of work is treated like a franchise and kept away from other creative minds.

But does Tolkien deserve this honor? Should we pull Tolkien from the world of fiction and throw him into the mythic cauldron?

Well, our opinions don’t matter, as it’s already happening- Tolkien is already in the pot, becoming myth, he is already in the public domain in every sense but the legal (the least important sense).

There is a staggering amount of work out there based on Tolkien.

Incredible poetry, and music, and art- and I mean really beautiful work, not your everyday “fan art”.

You can go to university to study Tolkien. What better evidence for his becoming myth could there be? Have you heard of George R.R. Martin studies? No? Well, Tolkien studies are a real thing, and are only taken more seriously with each passing year.

Alan Lee, Howard Shore, John Howe, Ted Nasmith- just a few names that have contributed some of the best music and art to our culture in decades, and without Tolkien we would have none of it.

The cultural impact of Middle-Earth is unparalleled. There are statues of its heroes, the Peter Jackson films are the most culturally significant and impactful films ever made, and “hobbits” or “halflings” might as well be as ancient an idea as elves and dwarves at this point.

But it’s not just that, it’s the way Middle-Earth is spoken of. In England people make jokes about Hobbits in the same way Scandinavians joke about elves- as if it’s just an ancient part of their culture, a reference everyone understands. Frodo, Gollum, Aragorn, these names are referenced more like folklore characters than names from a fantasy series. Tolkien references aren’t considered “nerdy” anymore, and this is a huge point even if it goes unnoticed. It shows that he is being integrated into the English mythos, and more broadly the entirety of European mythology.

Without him, the entirety of the English canon would be weakened- both the works that he inspired and the works that he drew his own inspiration from would be lessened without his contribution. Tolkien is the loadstar from which the entire modern conception of the mythic northwestern spirit springs from. Without him we would not have modern myth, modern “fantasy” as we know it would be completely different. Without his work, modern appreciation of Beowulf, the Eddas, the Volsungs, all of the ancient northwestern canon would be substantially weakened. Without him, even the modern conceptions of elves, dwarves, goblins and dragons that we take for granted would not exist.

He is English mythology.

Tolkien has even become politically relevant. The aesthetics of his work are symbols for traditionalists, reactionaries, conservatives, and even nature conservationists. In an era where the right-wing is fractured, Tolkien appreciation is one of the few uniting things left. Don’t think that I’m being hyperbolic- without Tolkien and without the Peter Jackson films, there would be a gaping hole in modern right-wing aesthetics and culture.

No other work of fiction is treated like this. This phenomenon is more akin to the treatment of Greek or Norse legends than to the treatment of normal fiction.

So it is high time we let Middle-Earth leave the realm of legal disputes, contracts, and movie studio negotiations and let it take its place among the rest of the European mythos. Let Aragorn and Frodo finally sit with Beowulf and Thor and King Arthur.

It’s high time we allow Tolkien to enter the public domain and be fully thrown into the great cauldron of myth and story.

Few stories deserve the honor of being thrown into the cauldron of myth.

The great tales of Middle-Earth are among those few.

One does not create a Mythology for England by oneself, and the Professor knew and said that.

Given he had to carry the burden single-handedly after all his other friends died, I think he would enjoy seeing modern day bards carrying on the epics.

Finally, a “Mythology for the English” would theoretically belong to The English and their descendants.

EDIT: Also, are there any other of us from Rohlin’s class in Substack who still want to write?

Excellent point pertaining to the music from the LOTR films. Appreciate you brother, that for which the heart of western man longs finds a refuge in your writings on Tolkien.